"There is often something beautiful, there is always something awful"

June 14, 2020

Black Lives Matter

If you’re reading this, I’m assuming this is neither a surprising nor particularly controversial thing to hear, but it scarcely seems responsible to hold a virtual microphone and not acknowledge the exceptional moment that we’re in right now. More than that - if you are white (like me) it ought to be another reminder that we need to do the active work of dismantling the white-supremacist system we have found ourselves benefitting from. Not simply renouncing it, but engaging in its destruction. Not merely being not-racist or “an ally”, nor asking for confirmation that we’re on the good team, but actively engaging in change. We need to do this work, and we need to not lean on our minority friends and family to prompt us, pat us on the head or, worse, continue to die in the streets to fix the problem we are in a position to address.

If there is a regret I have this particular month in this particular year, it’s being so far away from my home country where I feel like I could at least help hold the line. I keep re-reading Howl, which is so parodied (and so white!) as to perhaps seem irrelevant, but I miss my people and I read the texts from a family member helping build CHAZ an ocean away and I’m with you in Seattle, and I’m with you in Boston, and I’m with you in Minneapolis.

I’m with you in Rockland

where we hug and kiss the United States under our bedsheets the United States that coughs all night and won’t let us sleep

In my dreams you walk dripping from a sea-journey on the highway across America in tears to the door of my cottage in the Western night

If you are white and you haven’t seen I am Not Your Negro, you should make time for it right now. There is no shortage of contemporary black voices you should also listen to, but we need to grapple with our history in order to plan for the future. For me it was this film, and in particular the intense and uncompromising voice of James Baldwin that helped me understand that America has never acknowledged its black citizens as anything other than a problem to be contended with, and it will never properly heal until it does.

Baldwin: black, gay, exceptionally sharp-witted, died in France in 1987, when I was 9 years old and Reagan was president. I first encountered Baldwin as a note in history class (that fact is remarkable, but I’ll save that for another day), and again on a syllabus in college, but I didn’t really read, the way you read something that matters to you, until I moved to Switzerland and read Teju Cole’s New Yorker essay Black Body: Rereading James Baldwin’s “Stranger in the Village.”

I know nothing of the experience of being black, let alone black in America, but I do know something about being queer, and I do know something about being far away and in-between. And I know something about the perspective of geographic and chronological distance, which makes me feel simultaneously more and less capable of engaging with the place that made me.

The last time I was in Leukerbad, my partner Anindita and I dialed into a conference call to listen to the then-presumptive president Hillary Clinton address a group of volunteers at the women’s college Anindita (and Clinton) had graduated from. We’d attended the Obama inauguration together in 2009, a bitterly cold day with security problems that nearly left us stuck behind the same fences that currently ring the White House, and while I am hardly ignorant of the problems with both of those politicians and parties in general, the moment was historic and deeply emotional. And anyway, it’s better to pick your enemies when you can.

I explained the Republican candidacy at that time to European friends as the final convulsions of a cultural rift that started during the Civil War and never quite ended. I was a bit scared, but optimistic, I said, that the menacing white-supremacist voice needed to shout its own death rattle - that this would be close but we could move on. I was wrong on all counts. As Malcom X wrote: “You don’t stick a knife in a man’s back nine inches, and then pull it out six inches and say you’re making progress.”

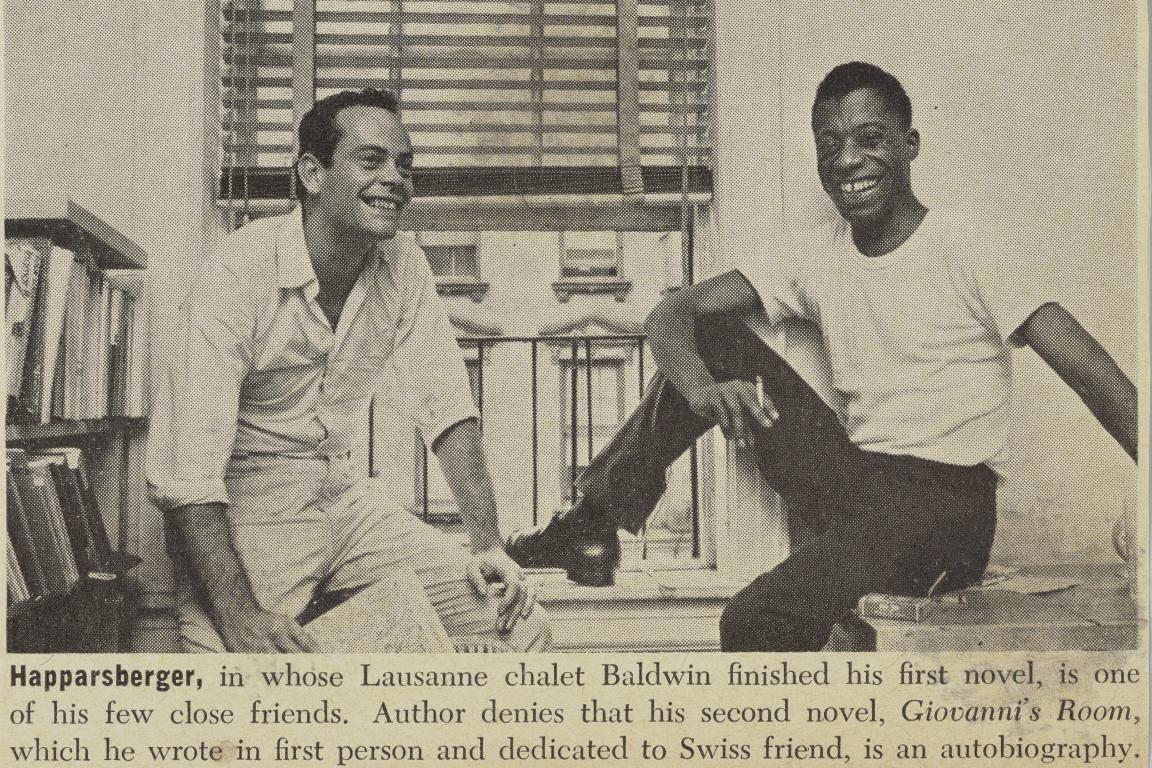

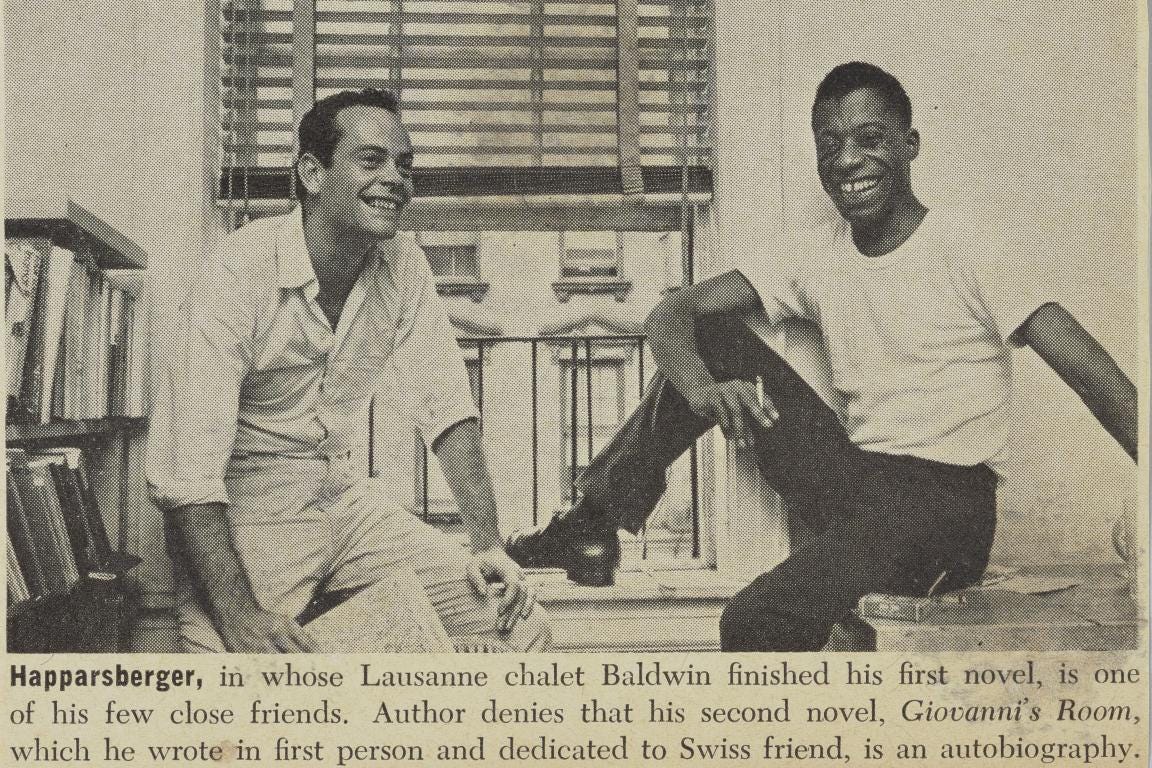

Baldwin wrote his 1953 Stranger in the Village (and Cole his own 2014 essay) in this same spot, a beautiful village which is home to the Klettersteig Daubenhorn, the largest via-ferrata in Switzerland (it is dizzying to look at from the ground, and obliquely referenced in Neal Stephenson’s Seveneves as a metaphor for sex with the boss, Markus Leuker). Baldwin was in Switzerland visiting his lifelong partner Lucien Happersberger, a white Swiss mountain climber and painter. The two had met in Paris three years earlier. Happersberger was bisexual and married to actress Diana Sands, although it was Baldwin who was at Happersberger’s bedside at Baldwin’s home in Provence when he died.

Baldwin wrote his novel Go Tell It on the Mountain at Happersberger’s mom’s chalet in Leukerbad (also called Loeche-les-Bains, sometimes misidentified as Lausanne.) The couple managed to convince Lucien’s parents to loan it to them by pretending that Lucien was recovering from tuberculosis: “I got X-rays of someone’s lungs from a student in medicine, took Jimmy with me, and we left for Switzerland. I showed these X-rays of ‘my lungs’ to my father, pretending I had been cured of tuberculosis and needed convalescence in the mountains. That’s how we got to Loeche-les-Bains, in my mother’s family chalet. My father sent fifty francs a week. It lasted all that winter if 1951. Jimmy re-wrote Go Tell It on the Mountain and finished it.”

The title of the novel famously memorialized the day when Happersberger and Baldwin went for a hike and Baldwin nearly fell off the mountain, steadied at the last second by Lucien. A book written an ocean away, under pretense of a feigned but very real respiratory illness. I thought about that near-fall later when Anindita and I took a wrong turn down a terrifying mountain path, accidentally picking ourselves along a cliff edge with our son on my shoulders, trying to make the last cablecar down before dark.

Nothing about this - nothing about Baldwin or his writing or the Swiss landscape, is easy or comfortable. Baldwin writes: “There is often something beautiful, there is always something awful …yet people remain people.” Like a hike along a cliff edge, his writing is exquisite and dangerous and scary. His novels are murderous, his voice unapologetically angry. His text is a fight, with the world and himself. As Hilton Als wrote in a 2007 essay about Baldwin’s unpublished letters:

As I read Baldwin in my present incarnation, I realized that he did not have a great formal mind. He did not have an expansive command of American history or politics. He wrote out of a sense of presumed intimacy with the reader, an early precursor to many of the memoirists currently in vogue. …He invented and reinvented himself, book by book. And through that invention he had grown dependent on his audience’s ability to make him feel complete, seen, known. I had learned from his example: the writer of delicate, precise talent who becomes a public figure, a spokesman, ceases to be the writer he meant to be.

Baldwin is impossible to ignore and impossible to engage on any terms but his own, even while he renegotiates these terms in front of us. To hear him speak, especially to a white audience, is to feel the tension and the fury, the palpable vibration that only sharpens his voice and his arguments. The gap between his crystalline phrasing and the squishy overfed ignorance where the words often land (interlocutors demonstrating the violence of their privilege by “politely” dismissing this terrifying intellectual whirlwind) is pure pain. Baldwin knows the unfairness and the impossibility of the task he never asked for, and in this situation he stands in the gap and holds his ground and demonstrates the only reasonable human response: sheer focused unflinching rage.

We’d feed him, and he’d come around at night. We’d have these very liberal political people over, and Jimmy, who’d embarked on his role as a preacher, used to stand in front of the fireplace and say, ‘Baby, we’re going to burn your mother-fucking houses down.’

And maybe sometimes, a walk in the Alps, steadied by a lover’s hand.

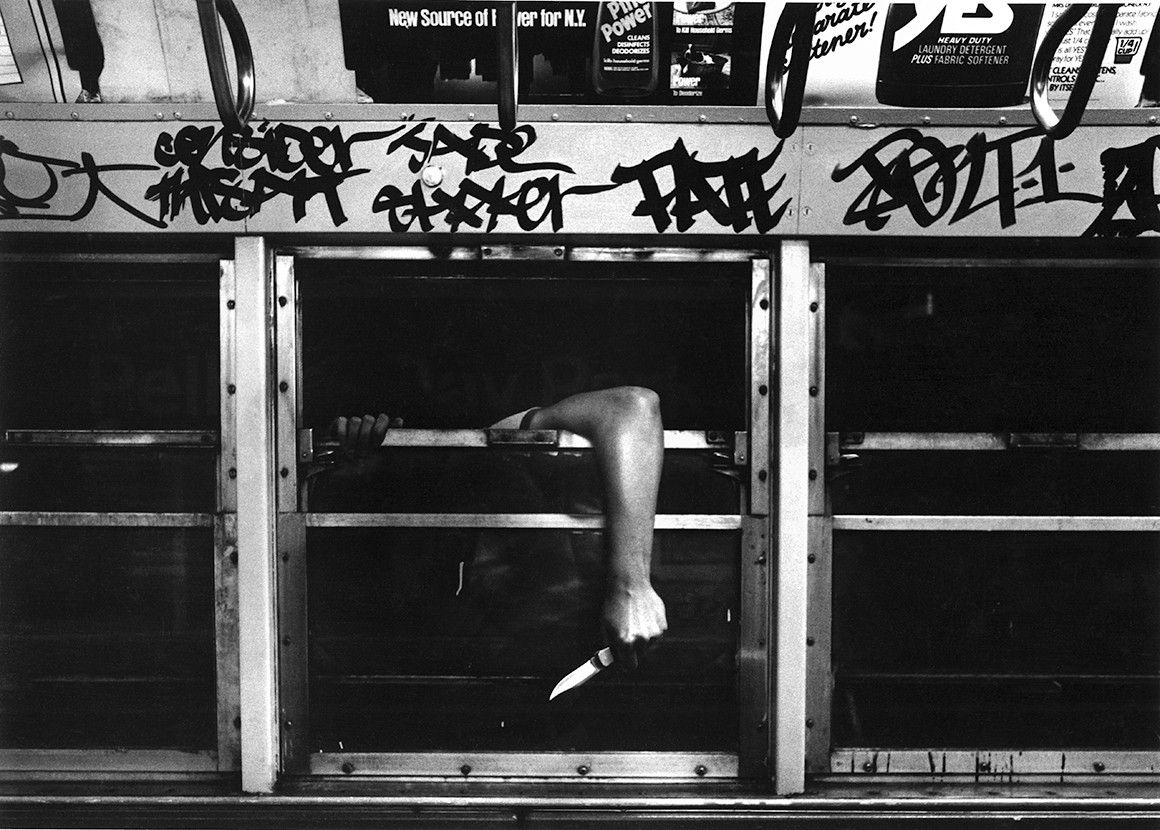

Edward Crawford, shown in this iconic 2014 photograph of the protests in Ferguson, recently became the third Ferguson protester to have died under suspicious circumstances in the back of a car. The story of this remarkable photograph is told by Crawford himself in the most recent episode of Criminal.

Of all the corners of the currently-ineffectual and largely irrelevant federal government, the US Embassy in Turkey posted this remembrance of James Baldwin on June 4th, 2020, specifically recognizing his LGBT contributions, while the US Government at home, in lieu of caring for its citizens, is concurrently taking steps to erase transgender rights, promote outlandish and dangerous conspiracy theories and host yet another racist revival meeting. Deaths from coronovirus are on the rise, the future is terrifying and uncertain, and it seems increasingly clear we’re not going to make it through this without each other.

Black Lives Matter.

———

A Song For June:

DEAD SKELETONS / DEAD MANTRA

“For me it was a spiritual battle song, because I have been HIV positive for 20 years, and the Dead Concept has grown out of that experience, my fear of death.

The first time I saw the doctor and was diagnosed [with HIV] was 1994, and I had had the virus since 1992. The times were different, they gave me three years. Oops, OK! So I thought 'fuck it', started drinking heavily and taking hard drugs like there was no tomorrow. I had to choose whether I wanted to die or live, and I took the decision to live. During that time the medication got better and better, though I could share stories with you about the medication for HIV. I remember one of them I was out of my head for two weeks…”